While I am no longer active at Blogspot, I do post substative articles regularly on SeekingAlpha (behind a paywall), and on Substack.

My substack posts so far in 2025:

-

Three Strikes and You're Out: Strategic Challenges of the US Auto Industry

– are they (GM, Ford, Stellantis Chrysler) out?"

July 19, 2025. -

Tesla in Europe: legacy makers are leaving them in the dust

... with production far below Berlin's "over 250,000" annual capacity

May 21, 2025 -

The Ascent of China's Private Car Firms

...and the collapse of its national champion State Owned Enterprises

May 13, 2025 -

Buy Here Pay Here: Paying Cash for Clunkers

– With A Nod to the New York Times

May 6, 2025 -

Reshoring: What it Takes to Build a New Factory –

Or why we won't see a rush of manufacturing returning to US shores

Apr 16, 2025 - Clunkers for Cash: The impact of tariffs on used car owners Apr 6, 2025

- The Trump Tariffs: A Great Inefficiency Machine – His tariffs will neither generate the desired revenues nor revitalize American manufacturing Apr 3, 2025

- China: A Price War? – maybe not! Discounting is rampant, but in line with changes in supply and demand Mar 21, 2025

- To Borrow or Not to Borrow: The Dilemma for USMCA auto manufacturers – Between Scylla and Charybdis Mar 5, 2025

- China Update: Tesla's Prospects – a precis of an article published yesterday on SeekingAlpha Feb 25, 2025

- Confusing Fast Followers with "IP Theft" – it's illusory to think that automotive technology is protected by patents Feb 7, 2025

- Tariffs and Automotive: no one in the industry has a 25% margin, and the supply chain is only as strong as its weakest link Feb 2, 2025

- Close the Border: The Impact's Modest – a simple insight from basic Econ 101 analysis on why drug interdiction does not work Feb 1, 2025

My most recent SA articles are:

- Tesla February Update: China And Europe Steady, But No Prospects For Growth, Mar 25, 2025

- Tesla China: Grim Prospects For CY2025, Feb 24, 2025

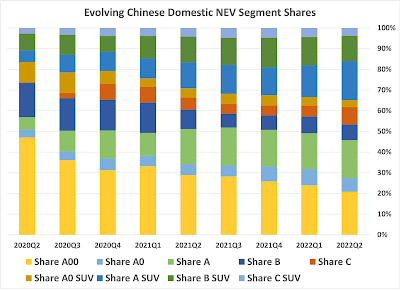

During COVID I learned to read Chinese, and have built a database of model-level domestic sales data for China covering over 1,000 light passenger vehicles, from January 2020 through the present. (I update data the middle of each month.) Each entry includes not just sales but also drivetrain, segment, brand, firm, price, and current discounts.

Along with the articles listed above, I have drawn on the database for a series of presentations at the annual GERPISA automotive research network conferences. While I've not finished sorting data, my presentation at the June 2024 GERPISA Bordeaux conference analyzed the geography of Chinese vehicle sales. I found that the sales of firms such as Guangzhou Auto but also Tesla exhibit a strong "home" bias. In contrast, BYD, VW, GM and Geely have strong sales throughout China.

On the GERPISA website you can find my analysis of the new model effect, the very similar size distribution of sales in China and Europe (eg, how important are the top 8 sellers in each market), how interactions between new and used vehicle markets explain COVID car price movements in the US, and the similarity in the geographic distribution of suppliers in China to those in North America and Europe.